When the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs slammed into the planet, the impact set wildfires, triggered tsunamis and blasted so much sulfur into the atmosphere that it blocked the sun, which caused the global cooling that ultimately doomed the dinos.

That’s the scenario scientists have hypothesized. Now, a new study led by The University of Texas at Austin has confirmed it by finding hard evidence in the hundreds of feet of rocks that filled the impact crater within the first 24 hours after impact.

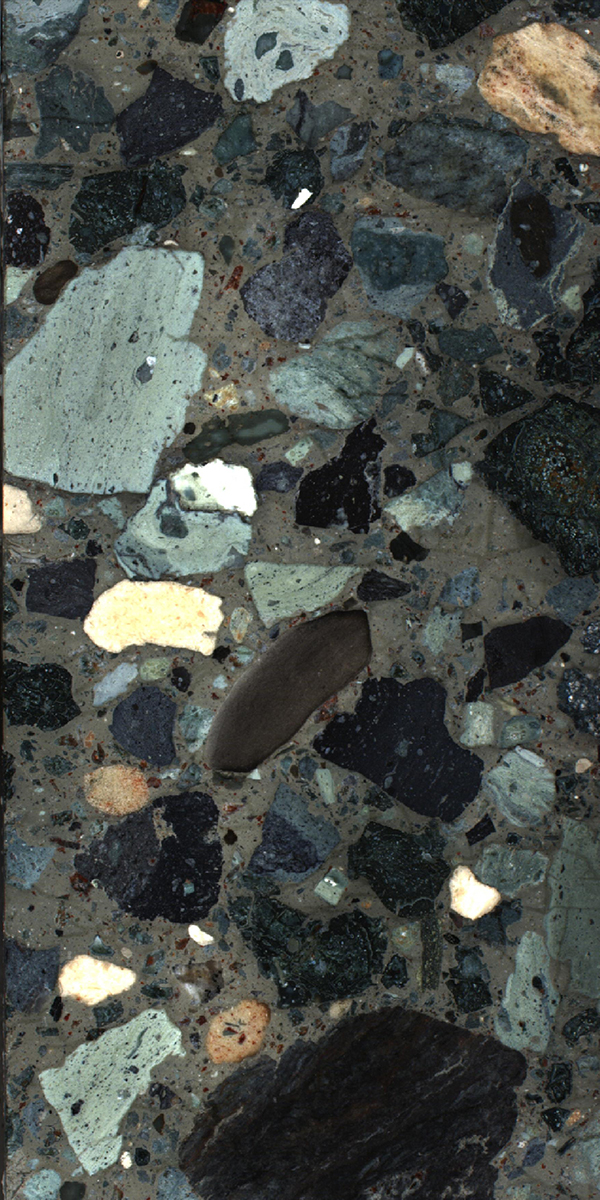

The evidence includes bits of charcoal, jumbles of rock brought in by the tsunami’s backflow and conspicuously absent sulfur. They are all part of a rock record that offers the most detailed look yet into the aftermath of the catastrophe that ended the Age of Dinosaurs, said Sean Gulick, a research professor at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) at the Jackson School of Geosciences.

“It’s an expanded record of events that we were able to recover from within ground zero,” said Gulick, who led the study and co-led the 2016 International Ocean Discovery Program scientific drilling mission that retrieved the rocks from the impact site offshore of the Yucatan Peninsula. “It tells us about impact processes from an eyewitness location.”

The research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Sept. 9 and builds on earlier work co-led and led by the Jackson School that described how the crater formed and how life quickly recovered at the impact site. An international team of more than two dozen scientists contributed to this study.

Most of the material that filled the crater within hours of impact was produced at the impact site or was swept in by seawater pouring back into the crater from the surrounding Gulf of Mexico. Just one day deposited about 425 feet of material — a rate that’s among the highest ever encountered in the geologic record. This breakneck rate of accumulation means that the rocks record what was happening in the environment within and around the crater in the minutes and hours after impact and give clues about the longer-lasting effects of the impact that wiped out 75% of life on the planet.

Gulick described it as a short-lived inferno at the regional level, followed by a long period of global cooling.

“We fried them and then we froze them,” Gulick said. “Not all the dinosaurs died that day, but many dinosaurs did.”

Researchers estimate the asteroid hit with the equivalent power of 10 billion atomic bombs of the size used in World War II. The blast ignited trees and plants that were thousands of miles away and triggered a massive tsunami that reached as far inland as Illinois. Inside the crater, researchers found charcoal and a chemical biomarker associated with soil fungi within or just above layers of sand that shows signs of being deposited by resurging waters. This suggests that the charred landscape was pulled into the crater with the receding waters of the tsunami.

Jay Melosh, a Purdue University professor and expert on impact cratering, said that finding evidence for wildfire helps scientists know that their understanding of the asteroid impact is on the right track.

“It was a momentous day in the history of life, and this is a very clear documentation of what happened at ground zero,” said Melosh, who was not involved with this study.

However, one of the most important takeaways from the research is what was missing from the core samples. The area surrounding the impact crater is full of sulfur-rich rocks. But there was no sulfur in the core.

That finding supports a theory that the asteroid impact vaporized the sulfur-bearing minerals present at the impact site and released it into the atmosphere, where it wreaked havoc on the Earth’s climate, reflecting sunlight away from the planet and causing global cooling. Researchers estimate that at least 325 billion metric tons would have been released by the impact. To put that in perspective, that’s about four orders of magnitude greater than the sulfur that was spewed during the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa — which cooled the Earth’s climate by an average of 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit for five years.

Although the asteroid impact created mass destruction at the regional level, it was this global climate change that caused a mass extinction, killing off the dinosaurs along with most other life on the planet at the time.

“The real killer has got to be atmospheric,” Gulick said. “The only way you get a global mass extinction like this is an atmospheric effect.”

The research was funded by a number of international and national support organizations, including the National Science Foundation.

For more information, contact: Anton Caputo, Jackson School of Geosciences, 512-232-9623; Monica Kortsha, Jackson School of Geosciences, 512-471-2241