When London Darce learned that the 2021 UT Marine Geology and Geophysics field course was going ahead, they jumped at the chance to make up for experiences they’d missed when the class was canceled early in the coronavirus pandemic.

“Hands-on fieldwork is vital, it’s what the geosciences are all about,” Darce said.

Darce, who is from Conroe, Texas, and studying for a degree in geophysics at the Jackson School of Geosciences, wasn’t the only student in this year’s cohort who was thrilled to be back in the field. Like Darce, Kazuma Sakamoto had hoped to get a taste of fieldwork in 2020, before the pandemic forced almost all field experiences to cancel.

His interest grew after he took on a research fellowship with UTIG engineering scientist Marcy Davis, one of the course instructors, where he helped add to a global map of the seafloor by processing and submitting multibeam bathymetry data for Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory’s Global Multi-Resolution Topography Data Synthesis, a map that is used by scientists and institutions worldwide (and even used in Google Earth!).

Working with real field data during that project left an impression on Sakamoto.

“It’s just mind-boggling that there’s so much to the ocean we have yet to uncover,” he said. The experience turned out to be a great introduction to field data and convinced Sakamoto to jump on the field course’s waiting list as soon as it became available.

Learning Expedition-scale Research Skills

The UT Marine Geology and Geophysics field course is unique from other field experiences because it puts students in the role of expeditionary scientists, which involves working with other scientists to collect diverse types of data on a research mission. UTIG, which organizes and runs the course, is known for leadership in expeditionary science, including the scientific cruise that drilled the dinosaur-killing Chicxulub crater, and a recent mission to locate a giant earthquake fault lurking in the northwest Pacific Ocean.

In the field course, students learn the techniques and manipulate the tools used by expeditionary scientists, but they also conduct original research with the data they gather, contributing to knowledge about coastal processes on the Texas Gulf Coast.

“It’s really very rapid-fire, hands-on, learning through a firehose kind of activity,” said UTIG research professor Sean Gulick.

Although the pandemic restricted class numbers for 2021, there were advantages to running a leaner class: aside from giving students more contact-time with instructors, the class was able to trial several new tools and research sites, including aerial surveys of the shore using a drone and using a vibracorer to sample salt marshes.

Lectures and Labs

As Darce and Sakamoto set out on May 23, 2021, for Port Aransas on the Texas Gulf Coast, they were joined by undergraduate students Marlowe Bueler and Davis Hagemeier, Jackson School graduate students Jake Burstein, Carson Miller, Solveig Schilling, and Chris Liu.

By then the students had already been introduced to the class’s main concepts and what to expect over the course of the following week. They learned the theory behind the geophysical instruments they would use and heard the Gulf Coast’s geologic history. They also became acquainted with the course instructors, who included Davis, fellow engineering scientist Dan Duncan, research scientist associate Steffen Saustrup, research scientists John Goff and Chris Lowery, and Gulick, the course director.

Another important aspect of the course was letting the students get their hands on industry-standard software that they would use to plan and navigate surveys, and process and interpret data.

Mobilization

After unloading the truck that carried their equipment to the coast from Austin, the first day was spent setting up and testing equipment and preparing the two boats from which the students do most of their field work: the R/V Scott Petty, a UTIG-owned research vessel designed for coastal waters, and the M/V Miss Vivian, a larger boat chartered for deeper-water surveys.

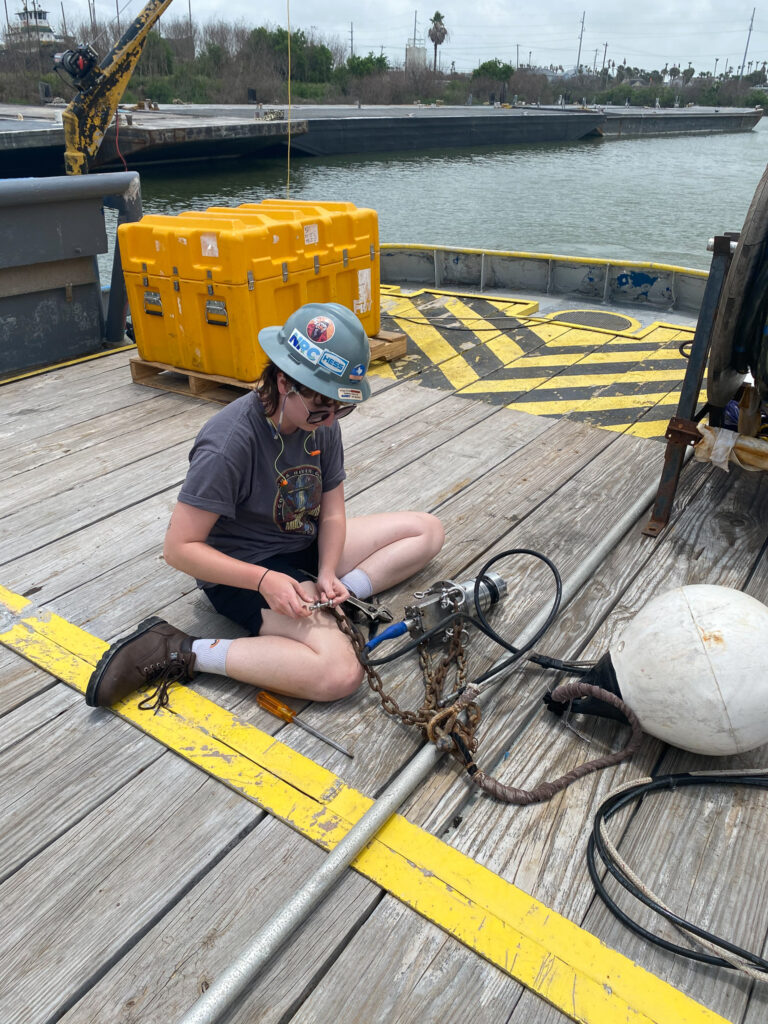

Darce assembles a seismic airgun on the M/V Miss Vivian.

Miller (left) and Darce carry equipment aboard the M/V Miss Vivian.

Bueler installing equipment on the R/V Scott Petty.

Burstein and Schilling working on the multibeam sonar. At sea, the instrument is mounted on the hull of the R/V Scott Petty, just below the waterline.

Getting gear ready for the R/V Scott Petty.

Field Operations

Students split into teams of two and headed out to gather their field data. Each of four mornings, the students went to sea, with two teams on the M/V Miss Vivian and two teams on the R/V Scott Petty.

On the M/V Miss Vivian, students deployed a CHIRP (an instrument that pings seismic waves into the upper tens of meters of seafloor), and a high-resolution “airgun” multichannel seismic system (similar in concept to the CHIRP but on a much larger scale for peering hundreds of meters beneath the seafloor).

The team recover the CHIRP during operations from the M/V Miss Vivian.

Students aboard the M/V Miss Vivian deploy a seismic streamer to investigate sediment layers buried hundreds of feet below the seafloor.

The M/V Miss Vivian allows for a small field lab where students help set navigation plans and check the data as it streams in. Left to right: Schilling, Hagemeier, Mueler, and Burstein.

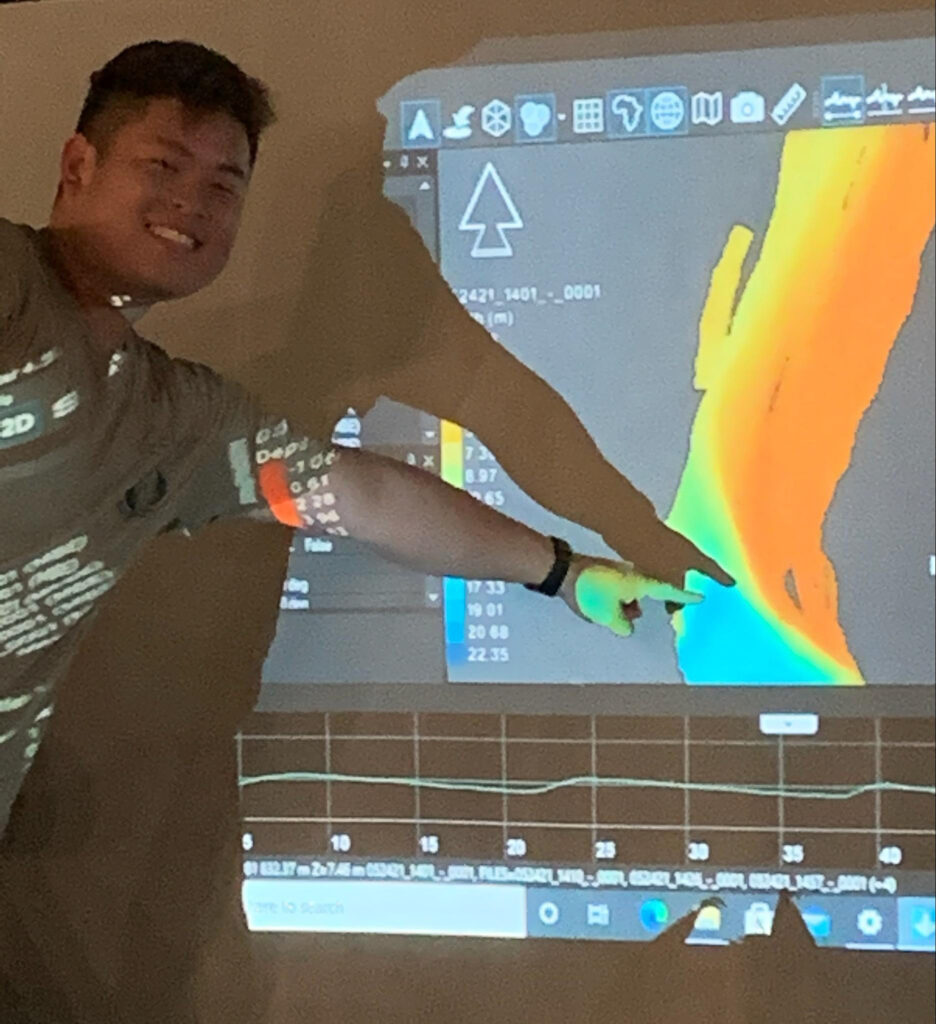

During the first two days aboard the R/V Scott Petty, students surveyed near Port Aransas using a multibeam sonar and a side scan sonar, both of which create high-resolution, information-rich maps of the seafloor. They also used a claw-like tool called a mini-Ponar sediment sampler for taking physical samples of the seafloor.

Over the next two days, students used the boat to ferry to Harbor Island where they used a vibracorer to sample marsh sediments as part of a collaboration with Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve.

The students also used the R/V Scott Petty as a base for launching drone flights over the Gulf Coast. The images the drone takes from above can be compared with satellite images of the area to see where the shoreline has changed.

A new activity in 2021 was a beach research excursion in which students surveyed the shoreline, learned how different parts of the beach formed and took measurements to watch for coastal changes in future years.

Burstein and Schilling take a breather between sites while surveying on the R/V Scott Petty.

They may be cute, but curious dolphins are drawn to the multibeam’s low-power sonar pulses. Miller recalls: “When we got back from mapping Lydia Ann Channel, we realized we were also mapping the dolphins and had to filter them out of the final product, which took quite a bit of time to do.” Credit: Carson Miller

Lowery explains coastal processes that shape the shoreline during a beachside lesson.

Shore Labs

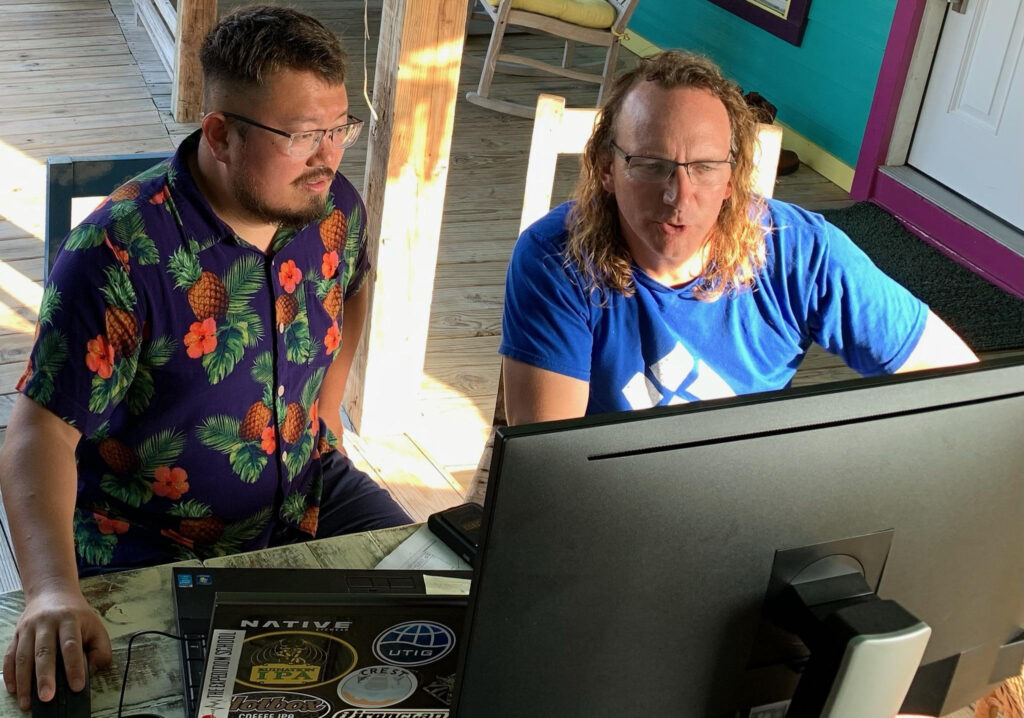

Most days, the morning was set aside for field work, with the afternoon and evenings assigned to processing and analyzing data onshore. Doing both on the same day helped the students understand the relevance of their field work and better understand the data.

Each evening students presented field reports informing other teams what they did that day. These also help teams plan for the next day and encouraged students to think about what their final projects will look like.

Saustrup (left) shows Darce how to clean and service the seismic airgun, a critical part of the high-resolution multichannel seismic system.

Liu and Gulick examine seismic data onshore.

Hagemeier, Burstein and Schilling examine a sediment core.

Hagemeier looks at foraminifera in a vibracore sample from the marsh on Harbor Island.

Sakamoto points to a feature in the multibeam bathymetry data during an evening field report.

The crawfish boil on the last night was among Burstein’s favorite moments. “It was great celebrating together (and winning the cornhole tournament with Dan Duncan!). Our smiles speak volumes to how happy we were to finally meet after a very long year.” Credit: Jacob Burstein

Presentation Day

As the teams packed up and headed back to Austin, Darce reflected on the experiences of the week. This wasn’t just a field trip to look at past geology, Darce’s project, which they’d decided would focus on the environmental impact of ship channels in Corpus Christi, had literally left them knee-deep in mud figuring out the impact of dredging on ecosystems, and what to do about it.

“I’m really excited to keep looking at complex issues like this,” Darce said. “It’s really shown me that the geosciences are about understanding and solving problems that affect us all.”

After a day’s rest, the students had just one week to interpret data and present their findings at a virtual meeting on June 7, attended by members of the Jackson School community, including field course alumni and industry sponsors. The talks, which ranged in scope from the immediate threat to coastal ecosystems, to the millennia-long march of barrier islands, were recorded and can be found in the section below.

Presentation day was the last day of the course. By the end, the students were exhausted but happy.

“It’s a very busy learning experience,” said Miller, “but I’m glad I took the course because where else are you going to learn how to collect, process, and interpret geophysical data within just two and a half weeks.”

Meet the Class of 2021

Carson Miller

“I’m glad I took the MG&G field course because I was able to see how to collect, process, and interpret geophysical data within a short time frame.”

Kazuma Sakamoto

“I chose this field course because it gets you the most hands-on experience with seismology data, which is my area of interest. It’s good experience for my future career plan.”

Christopher Liu

“The MG&G field course is a great experiential learning opportunity guided by a team of top-notch scientists.”

London Darce

“When my advisor told me that the Marine Geology and Geophysics field course was likely going to be in-person this year, I immediately jumped at the opportunity to regain lost experiences and do fieldwork.”

Solveig Schilling

“I chose to take the course because I want to gain experience understanding and interpreting marine geophysical and geological data. I also absolutely love being at sea!”

Andrew “Davis” Hagemeier

“I chose to take the MG&G Field course because it allows me to learn about different geophysical techniques that I am not very familiar with and also gain experience with working with and analyzing real data.”

Jacob “Jake” Burstein

“Before, most of what I’d learned had been theoretical, but this course showed me the true details of applied marine geology and geophysics. I feel it rounded out my geoscience knowledge.”

Marlowe Vaughn Bueler

“I took the course instead of the general geology field camp because I am interested in deep-sea studies, learning how to take cores from the ocean floor, and gain experience in geophysics.”

The 2021 Marine Geology and Geophysics Field Course Presentation Day talks were:

(follow links to the recorded talks)

Team 1: Carson Miller, Kazuma Sakamoto

Humans, storms, and climate drive geomorphic change

Team 2: Chris Liu, London Darce

Influences on Corpus Christi Bay’s Sediment Budget in Human and Geologic Timescales through Modern Industrialization and Buried Fluvial Channels.

Team 3: Solveig Schilling., Davis Hagemeier

Multi Temporal Perspective on the Evolution of the Aransas Bay area

Team 4: Jake Burstein, Marlowe Vaughn Bueler

Barrier Island Change Observed on Millennial and Yearly Timescales