UTIG Ph.D. student Enrica Quartini was inducted into UT Austin’s Friar Society this fall. The Friar Society is the oldest honor society at the university and welcomes only a few new student leaders each semester. We sat down with Enrica to learn more about her studies and research at UTIG and her passion for Science Olympiad.

What led you to study at UTIG for your Ph.D.?

What led you to study at UTIG for your Ph.D.?

Growing up in Italy, my parents and I often experienced temblors. The whole house shook when an earthquake struck and I was terrified. I believe that’s what got me interested in the phenomenon—I wanted to understand so I would be less fearful. Later on I learned that Italy is part of the African tectonic plate and it is smashing into Europe. That explains the seismicity and Italy’s many active volcanoes.

My fascination with earthquakes and volcanoes led me to the Universitá di Bologna where I earned a bachelor’s and master’s degrees in geological science. During my first year as a master’s student, I was awarded a Trans-Atlantic Science Student Exchange Program scholarship to study in the United States. My objective was to improve my English and challenge myself to live abroad. The scholarship allowed me to choose from a list of universities. My undergraduate advisor, a seismologist who had spent time in California, was excited for me. He thought it was a great opportunity, reviewed the list, and said, “Pack Your bags. You’re going to UT Austin.”

I arrived at UT Austin and, under Jack Holt‘s direction, began researching the presence of ice on Mars using satellite radar. That year of research became my master’s thesis. No sooner had I returned to Italy when Don Blankenship invited me to return to UT Austin to pursue a Ph.D., studying subglacial volcanoes in Antarctica. And here I am at UTIG working under the supervision of Don and Duncan Young.

What are you currently researching?

My thesis is on subglacial volcanic activity in West Antarctica and its impact on ice sheet stability. There is a big heat anomaly in West Antarctica, which is why there are so many volcanoes. They are covered by thousands of meters of ice so the only way to study them is with indirect methods such as radar and potential fields. Basically, I’m interested in understanding how the heat from volcanic activity underneath the ice in West Antarctica can contribute to phases of collapse and regrowth of the ice sheet in that region.

What is your favorite part of your research? And what have you learned from doing it?

I loved learning about radar from the Mars research project. I used it to find buried ice under the many debris flows in the mid-latitudes of Mars. The whole field of radar/electromagnetic waves is fascinating and a superb example of how physics can be used to study geological processes. As a child, I could never have imagined that I would apply remote sensing technology to study volcanoes while flying across Antarctica. It’s exhilarating!

I’m a hands-on person so field work appeals to me. As a Ph.D. student at UTIG, I’ve had the opportunity to have ownership of a project—defining the problem, developing the approach and methodology, selecting the targets, designing the geophysical survey, collecting and analyzing the data, and presenting results. All our studies are hypothesis driven, and must take into consideration that we are working in an extreme environment. Therefore we allow for contingencies in our pursuit of the best science.

In Antarctica, different nations administer their own research stations. We work with many of them and must be sensitive to the cultural norms and the different ways they approach operations. It is an excellent lesson in learning the value of mutual respect that underpins all international collaborations.

When we go to Antarctica, our goal is to have as boring a field season as possible: boring means no unpredicted issues, no losses, no crises. The fact that so far we’ve never had to prematurely or unexpectedly end a field season speaks highly of the structural and operational philosophy of our group. As Ph.D. students, we are brought into the planning and decision making early on, reinforcing the notion that each person plays an important role. I am lucky to have learned from the best.

What is your most memorable fieldwork experience?

Last year was a particularly challenging field season in Antarctica. Fellow graduate student Laura Lindzey and I, together with our field engineer, Dillon Buhl, co-led an airborne geophysical survey on a new platform—a helicopter instead of the usual fixed-wing Basler airplane used to do surveys in Antarctica. Helicopters are frequently used for airborne gravity and magnetic surveys but had never before used for other kinds of remote sensing, such as radar and laser altimeter. We first went to New Zealand to train with the helicopter company to figure out what could and could not be done. When we finally went to Antarctica, after a 8-day long journey on an ice breaker, we mounted a geophysical survey that met all our science goals and more, exceeding expectations. It was rewarding and empowering.

You have played a huge role in growing Science Olympiad at UT Austin. What interested you in the program?

When I first moved to the US the biggest cultural surprise was learning about the division of public schools into districts and that students go to school in the district they reside. This was new to me since in Italy you can attend any high school you want. When I learned about school districts I realized that if I had been born and raised in the US with my family’s limited resources, I might not have received the same level of education or access to the opportunities I had in Italy.

This motivated me to get into outreach—to reach kids who are in Title 1 Districts, those serving historically underserved populations. I was determined to put my enthusiasm for learning to use. I’ve dedicated my efforts to Science Olympiad for the past 6 years for two main reasons.

First, Science Olympiad impacts a large pool of students. Science Olympiad is the largest team-based STEM program in the nation. The rules I write as a national supervisor in the Earth and Space Science Olympiad committee engage over 200,000 students nationwide and help shape their science literacy.

Secondly, I care deeply about gender equality and I believe Science Olympiad is the best cross-gender team-based STEM outreach program in the nation. In practices and competitions, I see young girls develop courage and independence, realizing the power they have to solve problems and support their team equal to or better than their peers. Science Olympiad is helping us increase the participation of women in STEM fields. Moreover, and very importantly, Science Olympiad is helping the next generation of men break the cycle of stereotypes about women’s role, ability, intellect, presence, and worth both in the workplace and in society.

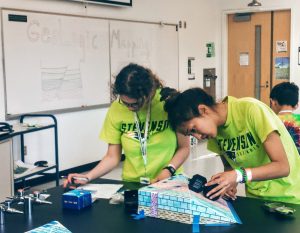

In 2014 funding from our previous sponsor ended, threatening the future presence of Science Olympiad at UT. With the generous support from UTIG it was possible to continue Science Olympiad. I am honored to be member of the leadership team that administers UT Austin Science Olympiad Regional and Invitational Tournaments and to see it continue to flourish. To date we have organized six tournaments at UT Austin and welcomed more than 900 high and middle school students, assisted by hundreds of UT undergrads volunteers every year.

What’s next for Science Olympiad here in Austin?

Here at UT Austin we have established a student organization called Longhorn Science Olympiad Alumni Association. Many of the students in the organization are former Science Olympiad competitors who want to give back to the organization by serving as mentors for younger students or write tests for our tournaments.

Through the student organization we are now working on starting new Science Olympiad teams in Title I schools in Austin. We want to go to historically underserved schools with money, resources, and mentors to help them start teams.

My personal goal has always been to reach out to those very students. With support from the KDK-Harman foundation, we have started two competitive Science Olympiad teams in Title I schools and are facilitating the growth of 8 others, but this is just a start! Having our own tournament here at UT Austin is essential as it provides a local and protected playground for these new teams to grow and build their team identity and confidence. The program we are leaning on is called Urban School Initiative which has been successfully piloted in Chicago. We want to make it successful across Texas.

You were recently inducted into the Friar Society, the oldest honor society at UT Austin. What does it mean to you to be a member?

I was honored to be recognized for projects I’ve put effort and passion into over the past 6 years, both in the fields of airborne geophysics and STEM education.

It is humbling to be part of such an old society composed of individuals from across all disciplines. It is invigorating and enlightening to meet people from diverse backgrounds who share their motivations, experience, and stories.

Writer Chimamanda Adichie says in her TED talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” there isn’t only one story that describes us all. Indeed there are many motivations and multiple pathways to do good. It is incumbent to us to pay attention to everyone’s story so that we can better participate in our ultimate common effort.

What do you hope to do after you graduate?

I like the managerial aspects of big operations—identifying and leveraging people’s technical and character strengths across disciplines and cultures to optimize performance and improve positive flow. After graduation, I want to dedicate myself to science management and operation.

It is also going to be essential for me to be able to continue my work in science education and outreach as this has become an integral component to my life, one that keeps me striving, enthused, and fulfilled.