The Issue

One of the biggest problems with studying Mars is that many of the things scientists are interested in — biomarkers, carbonates, and signs of ancient life — are trapped inside the planet. By locating sites on Mars where erosion is most active, scientists let glaciers do the digging and, in turn, increase chances of scientific discovery.

The Research

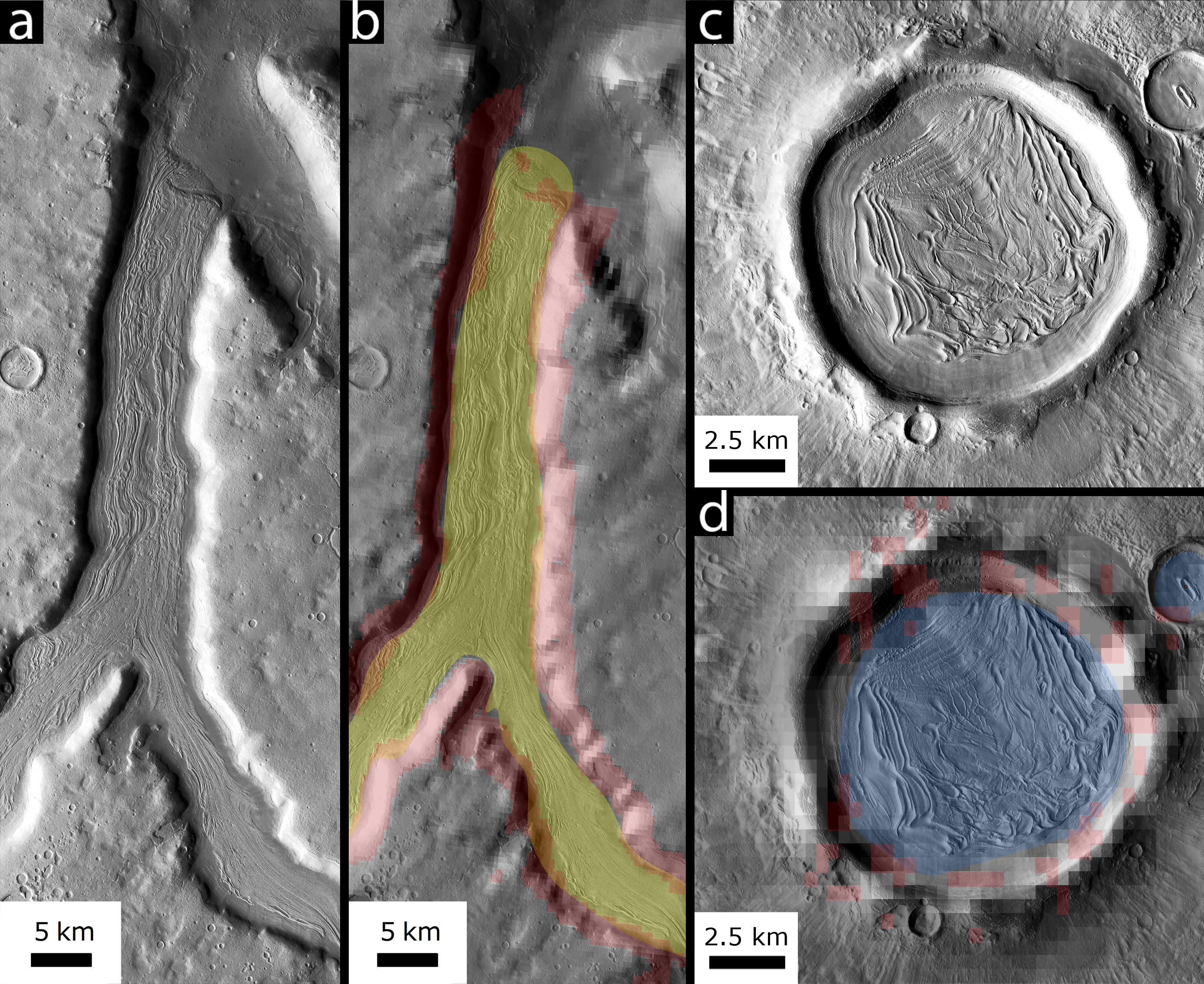

Looking at the surface of Mars, all we see is red rock. Yet underneath the top layer of soil and rubble are thousands of hidden glaciers, slowly carving away at the planet, some hundreds of kilometers thick.

Based on previous understandings of Mars’ erosion rate — approximately one atom per year — the amount of debris covering these frozen giants didn’t make sense to Joseph Levy, Research Associate at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG).

“All of that rock that’s now on the glaciers didn’t start its life there. It started off as part of some cliff upstream,” says Levy. “How did all this rock get from the mesas and the valley walls to be on top of these Martian glaciers?”

Levy, along with colleagues Caleb Fassett from Mount Holyoke College and James Head from Brown University, were mapping Martian glaciers when they made a quick “back of the envelope calculation” that revealed the volume of the debris covering the glaciers was too high for the erosion rate to be so slow.

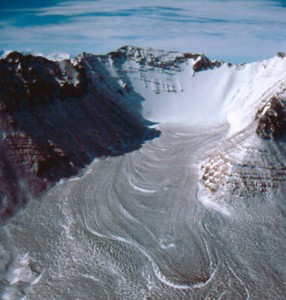

Their research, “Enhanced Erosion Rates on Mars During Amazonian Glaciation” published in Icarus, posits that erosion rates may be thousands of times faster than previously believed. Even at that rate, Mars’ erosion is still slower than anywhere on earth outside of deep freeze in the Antarctic cold desert.

“Erosion isn’t happening one atom at a time, it’s happening one boulder or one sand grain at a time. There is a lively and dynamic process of giant rocks moving around,” says Levy. “It’s a good reminder that Mars is an Earth-like planet, but still an enigma. The fastest erosion rates on Mars are similar to the slowest eroding places on Earth. The places with the most freshwater on Mars are equivalent to the saltiest waters on Earth. We have these two planets meeting at extremes.”

For the Layperson

At the end of October, NASA scientists will meet to discuss the location of the first human landing site on Mars. Levy and his colleagues will be in attendance to remind decision makers that glacial landscapes are great human targets because of the potential diversity found in fresh outcrops.

“The flat places on Mars where we’ve sent initial rovers are great landing sites, but they’ve sat unchanged for three or four billion years. Anything interesting has been destroyed by radiation or meteor impacts,” Levy says. “But if we go to one of these steep, glacially carved parts of Mars we stand a much better chance of finding something brought to the surface by erosion that is geochemically or astrobiologically more interesting.”

The Study

Enhanced Erosion Rates on Mars During Amazonian Glaciation