The final UTIG seminar this semester will be given by UTIG grad students Allison Lawman, Tianyi Sun and Sophie Goliber. We asked each student to give us a little sneak-preview into what they’ll be talking about and why they’re excited about sharing their research with the science community.

The seminar takes place at 10:30am (CST) on Friday, November 30 at UTIG. Click here to watch the seminar online.

Name: Tianyi Sun

Degree: Geological Sciences PhD

Funding: Ewing-Worzel Graduate Fellowship

Expected graduation: 2019

Hi Tianyi. I’m told you’re giving a presentation at this week’s UTIG seminar. Do you mind telling us what you’ll be talking about?

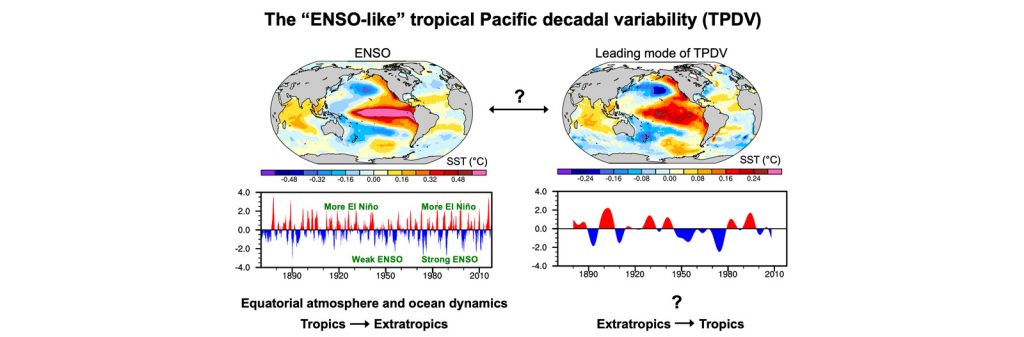

My title is “Role of Stochastic Atmospheric Forcing in Tropical Pacific Decadal Variability and ENSO Modulation”.

That sounds complicated. What’s that exactly and where does it happen?

So basically I’ll be talking about climate variability in the Pacific Ocean on a timescale that is between ten years and a hundred years, what we call interdecadal variability. The kind of variability I’m looking at is changes in sea surface temperatures and I’m particularly interested in the tropical Pacific.

Why is interdecadal climate variability so important?

Global warming isn’t steady even if you look at mean temperatures: sometimes they rise slowly, sometimes fast. This is why global temperatures didn’t increase as rapidly as predicted by some models during the late 90’s and early 21st century. We spend a lot of time studying centennial timescale climate changes (so things like anthropogenic climate change), or interannual timescales (for example, El Nino and La Nina) but there is a lot of uncertainty about climate changes on interdecadal timescales. In other words what kind of climate patterns do we see at timescales of 30-70 years? They are important because they can exhibit climate changes that are quite different to the global mean and studying them helps us understand how the climate works and how it might change.

OK, that sounds important. What else can you tell me about it?

These interdecadal temperature changes can also affect the frequency and amplitude of El Nino and La Nina events, which are known to cause floods and droughts all over the world. They are also difficult to predict so we are trying to understand what’s happening to help make better predictions about how the climate will change over the next decades.

How do you predict something like that?

We can’t really predict it if we don’t understand what causes the changes in ocean temperature in the tropics in the first place. Outside of the tropics, a theory called Stochastic Climate Model works well. Our atmospheric circulation has large patterns at specific geographic locations, say a low pressure system sitting over the North Pacific. It doesn’t move much in space but it varies randomly in time, strengthening and weakening like a white noise. The underlying ocean can’t change its temperature as fast as the atmosphere circulation, because of its thermal inertia. As a result the ocean preserves some low frequency variations. But we don’t how these slow variations in ocean temperature propagate from the extratropics into the tropics, and that’s what we are trying to figure out.

Good luck with that! But wait, what does this all mean for Texas?

So for Texas, we know that El Nino tends to bring rain to Texas and La Nina brings drought. If this interdecadal climate variability we are talking about affects how severe El Nino and La Nina events can get, how often they happen, and how long they can persist, it really matters for agriculture and food security. During the late 90’s and early 21st century, the tropical Pacific remained slightly cooler and as a result Texas suffered many long lasting droughts caused by long lasting La Ninas. It’s been recovering since 2013 but this could happen again when the tropical Pacific enters another cold regime in the future.

How do you feel about giving a UTIG seminar?

I’ve given conference talks to other people who are in my area, but this will be the first time I’ve given a talk to a broader science audience. The real challenge is to explain the problem in a way that the people who are not in my field can understand it but at the same time it won’t be boring for those who are in my field! A big inspiration for me is a very popular climate scientist called Clara Deser, who works at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. The first paper I read when I came here was her review paper, and I still read it every few months. The way she describes things is pretty special. She speaks very efficiently, very slowly and in a way that’s hard to believe she can cover so much material but she never says a word that isn’t meant to be there. I learned a lot from her.

Want to know more about Tianyi? She spoke to us earlier this year about studying at UTIG and being recognized by the American Meteorological Society.