It takes at least 10 million years for life to fully recover after a mass extinction, a speed limit for the recovery of species diversity that is well known among scientists. Explanations for this apparent rule have usually invoked environmental factors, but research led by The University of Texas at Austin links the lag to something different: evolution.

The recovery speed limit has been observed across the fossil record, from the “Great Dying” that wiped out nearly all ocean life 252 million years ago to the massive asteroid strike that killed all nonavian dinosaurs. The study, published April 8 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, focused on the later example. It looks at how life recovered after Earth’s most recent mass extinction, which snuffed out most dinosaurs 66 million years ago. The asteroid impact that triggered the extinction is the only event in Earth’s history that brought about global change faster than present-day climate change, so the authors said the study could offer important insight on recovery from ongoing, human-caused extinction events.

The idea that evolution – specifically, how long it takes surviving species to evolve traits that help them fill open ecological niches or create new ones – could be behind the extinction recovery speed limit is a theory proposed 20 years ago. This study is the first to find evidence for it in the fossil record, the researchers said.

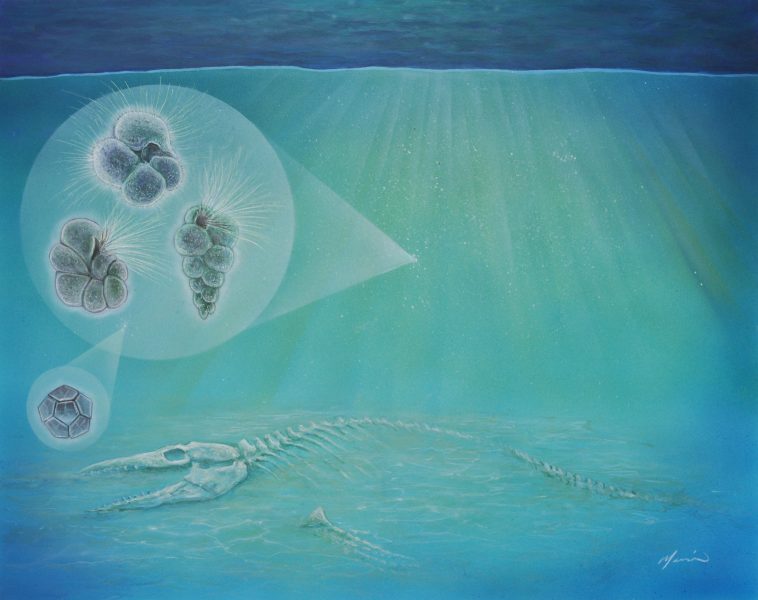

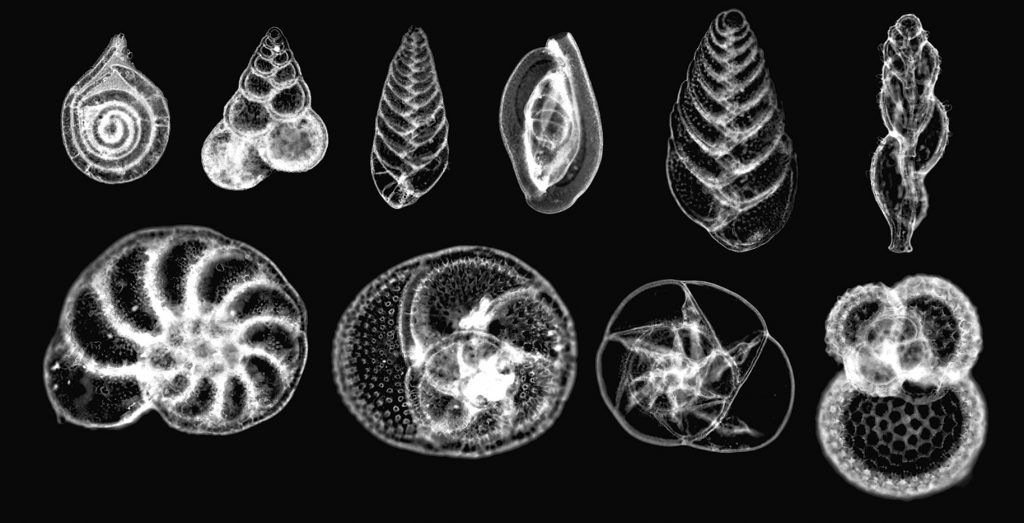

The team tracked recovery over time using fossils from a type of plankton called foraminifera, or forams. The researchers compared foram diversity with their physical complexity. They found that total complexity recovered before the number of species – a finding that suggests that a certain level of ecological complexity is needed before diversification can take off.

In other words, mass extinctions wipe out a storehouse of evolutionary innovations from eons past. The speed limit is related to the time it takes to build up a new inventory of traits that can produce new species at a rate comparable to before the extinction event.

Lead author Christopher Lowery, a research associate at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), said that the close association of foram complexity with the recovery speed limit points to evolution as the speed control.

“We see this in our study, but the implication should be that these same processes would be active in all other extinctions,” Lowery said. “I think this is the likely explanation for the speed limit of recovery for everything.”

Lowery co-authored the paper with Andrew Fraass, a research associate at the University of Bristol who did the research while at Sam Houston State University. UTIG is a research unit of the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

The researchers were inspired to look into the link between recovery and evolution because of earlier research that found recovery took millions of years despite many areas being habitable soon after Earth’s most recent mass extinction. This suggested a control factor other than the environment alone.

They found that although foram diversity as a whole was decimated by the asteroid, the species that survived bounced back quickly to refill available niches. However, after this initial recovery, further spikes in species diversity had to wait for the evolution of new traits. As the speed limit would predict, 10 million years after extinction, the overall diversity of forams was nearly back to levels observed before the extinction event. Foram fossils are prolific in ocean sediments around the world, allowing the researchers to closely track species diversity without any large gaps in time.

Pincelli Hull, an assistant professor at Yale University, said the paper sheds light on factors driving recovery.

“Before this study, people could have told you about the basic patterns in diversity and complexity, but they wouldn’t have been able to answer which one is leading or how they relate to one another,” she said.

The authors said that recovery from past extinctions offers a road map for what might come after the modern ongoing extinction, which is driven by climate change, habitat loss, invasive species and other factors.

For more information, contact: Anton Caputo, Jackson School of Geosciences, 512-232-9623; Monica Kortsha, Jackson School of Geosciences, 512-471-2241