Sand is in the concrete that holds up our buildings and lines our roads. It’s in the screens of our phones and the glass of our windows. And billions of tons of it are used to protect coastal communities from erosion, sea level rise and the impact of major storms. But you can’t just use any old sand. It’s imperative that grain size fits the project at hand.

Ongoing research led by the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) is helping the state to better understand its sand resources by taking inventory of the sand in ancient river valleys that are now buried below the seafloor offshore of Galveston. When sea level was lower, sands were deposited in these valleys by meandering rivers, and then buried and preserved by bay muds as sea level rose.

These deposits represent a very large potential resource of commercially and environmentally useful sand.

The project is funded by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. The UTIG researchers leading the project are Senior Research Scientist John Goff, Research Professor Sean Gulick and Research Associate Christopher Lowery. The goal of their research is to develop an inventory of the location, character and quantity of the sand resources found in these valleys.

“It’s harder to find these things when they’re not just sitting on the sea floor,” Lowery said. “So, we go out and survey and actually map them.”

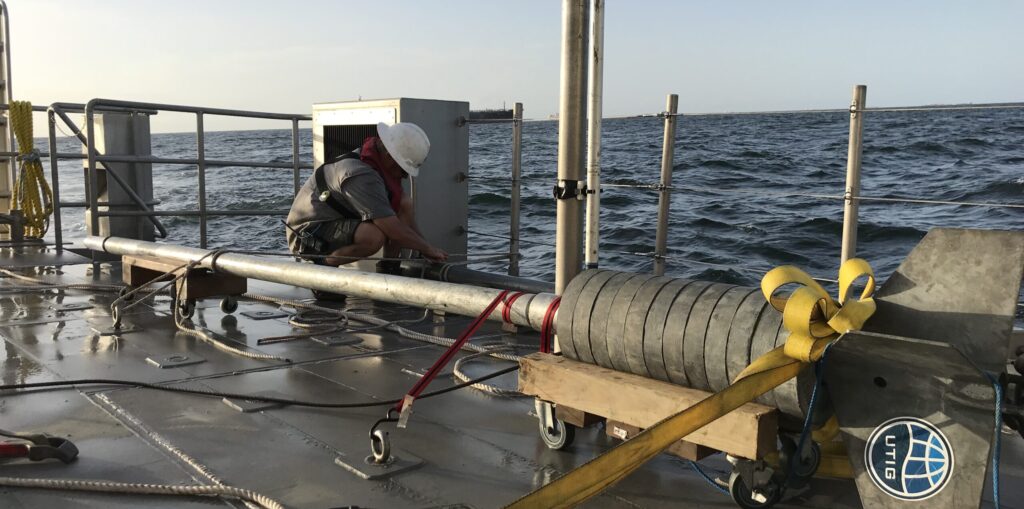

Their most recent surveys have focused on the sand deposited long ago by the Trinity river. UTIG scientists are using seismic surveys and core samples to locate the extent of the ancient river system and estimate the volume and type of sand it holds.

As part of this work, UTIG scientists are studying how past sea level rise changed sediments in the ancient bay. Sandy deposits in estuaries are often linked to specific environments like river deltas or fans that form behind barrier islands. Understanding how these features developed during times of sea level change is essential to pinpoint the location of the sand. The same idea can be used to predict what might happen in the modern Galveston Bay as sea level rises today.

As part of the project, UTIG has teamed up with Jackson School alumnus Bobby Reece, who is now an assistant professor at Texas A&M University, to test the use of a high-resolution seismic imaging device called a SPARKER that should have the necessary frequencies to map the base of the buried river valley. If the SPARKER works, the team plans on partnering with Reece to map other rivers in Texas.