By Constantino Panagopulos

It is December, 2018, and Repsol has just signed to rejoin the Gulf Basin Depositional Synthesis (GBDS) program, an industry-supported study of the Gulf of Mexico spearheaded by The University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG). Program director John Snedden knows that the Spanish energy giant’s return to GBDS not only marks the end of a long downturn but also confirms the success of GBDS’s survival strategy. That’s because Repsol’s return is about more than just an uptick in oil prices. It is testament to years of innovation at GBDS and a greatly expanded scope since 2011.

“Oil and gas is a very cyclical business,” explains Snedden, who is also a UTIG senior research scientist. “During twenty-four years of continuous industry funding we’ve seen multiple up and down cycles. Our ability to weather the latest cycle lies in several important innovations that have allowed us to broaden and expand our scope.”

This is the message that Snedden and the GBDS research project team hope to convey to industry members at the GBDS annual meeting in Austin on January 17.

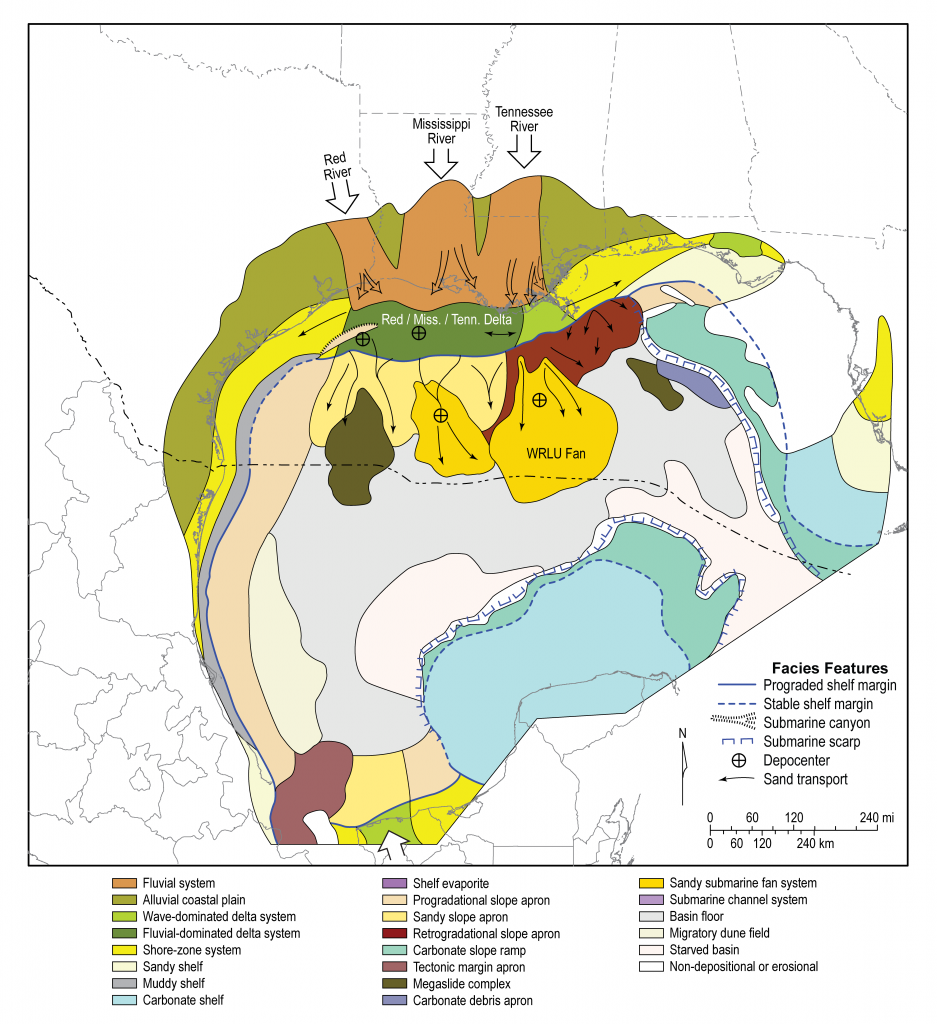

GBDS was launched twenty-four years ago to help oil and gas companies reduce overall risk and uncertainty when drilling. As the name suggests, the main focus of the program’s work is to gather knowledge about the depositional history of the Gulf of Mexico, in other words creating a data set about the layers upon layers of sediment buried beneath the Gulf. This data set manifests in the program’s primary scientific product: the GBDS Phase XII Atlas – a series of detailed maps, cross-sections, and reports on the basin’s depositional history.

Snedden explains that offering companies geological context for exploration is what the program does best.

“We provide play level context for exploration,” says Snedden, referring to the reservoirs of oil and gas created by complex geological conditions. “When a company considers a new prospect, our data helps put that prospect into regional context and provides insights about the reservoir. This helps companies reduce risk and uncertainty.”

Becoming a member gives access to GBDS’s easy-to-use database of maps, cross-sections and rock analyses and is a relatively inexpensive way for companies to drastically improve oil and gas exploration. When times are tough, however, tangible costs such as consortia funding are often the first to be cut. This meant that GBDS had to be sure they offer existing members an increasingly valuable product while also attracting clients in new markets.

One way of doing this was to expand their scope of interest to include the southern Gulf of Mexico which only recently became available to international exploration. Interestingly, this is also why Repsol returned to the fold.

Like many Gulf oil and gas exploration companies, when oil prices fell sharply in 2015 Repsol was forced to scale back Gulf activities. Now four years later, Repsol is once again increasing production in the Gulf and has turned to GBDS because it offers detailed, regional mapping of the southern Gulf of Mexico, something no other academic research project currently does.

Although authorities opened up Mexican waters to international exploration in 2015, low oil prices and technical difficulties in finding and accessing resources in this area mean that this region of the Gulf has remained relatively underexplored in comparison to US waters. Data provided by GBDS has been a game changer for successful drilling in other parts of the basin so it makes sense for companies to turn to GBDS when they want to know where to explore and what to expect when drilling new wells. Now even Mexican state institutions are looking to partner with GBDS and other UT expertise to increase their oil production in the region.

“A number of companies only explore the Mexican waters of the Gulf,” says Snedden. “Repsol came back because we showed them how much new work we were doing in this region.”

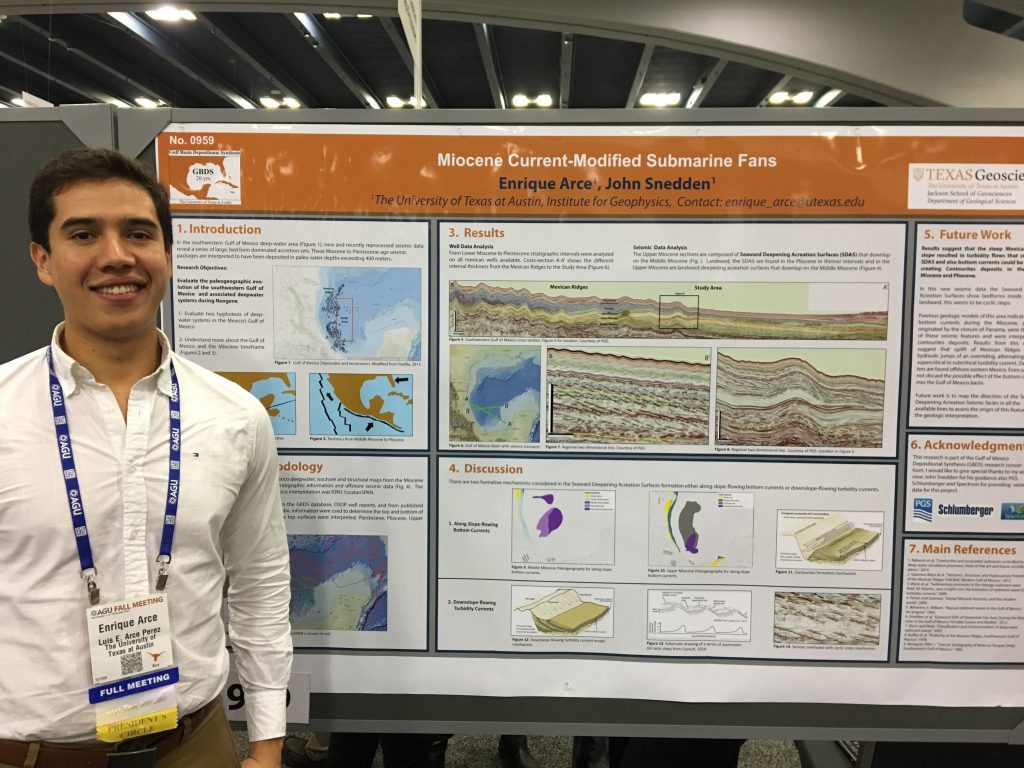

This includes work by UT graduate students such as Fernando Apango Perez, whose expertise with data sources held in Mexico has helped greatly in the program’s expansion in the region. Other UT graduate students from Mexico or South America have also contributed to GBDS research in the past including Enrique Arce Perez, Mario Gutierrez and Luciana de La Roche Tinker. All have presented their research to companies that support GBDS. The opportunity to speak to large, high-level audiences is a significant moment in the careers of these young scientists and demonstrates that GBDS is about more than just maps – arguably its most significant contribution is training the next generation of geoscientists. Several students, including Tinker and Gutierrez, have even been hired by the companies to which they presented.

Another well-known GBDS alumnus whose contributions to science have earned worldwide recognition is Chris Lowery, a biostratigrapher who began a fellowship with GBDS in 2015 and was recently hired by UTIG as a research associate. Lowery’s work with GBDS and UTIG took him to the crater created by the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. Lowery’s expedition to the Chicxulub crater in the Gulf of Mexico revealed that life recolonized the impact site less than a decade after the asteroid struck, much sooner than previously believed.

Of course, generating maps of the southern Gulf is not the only way GBDS has weathered the recent downturn. Snedden highlights program innovations such as digital seismic data from across the basin, original analyses of well samples and source rock, and research to make use of valuable information from a special group of minerals known as zircons found deep beneath the Gulf. This last data source is possible because GBDS has access to a world-class zircon lab run by Daniel Stockli at the UT Jackson School of Geoscience.

“Detrital zircon provenance work is really cutting edge science,” explains Snedden. “These little geo-thermometers of Earth history tell us very important things about the sandstones in which they are found, including where they came from. If you know where they come from then you know how they got there which can help you determine what else is down there. This is especially important in pre-salt mapping of the basin.”

The pre-salt layer is the part of the crust found beneath layers of salt laid down in the Earth’s distant past. Large salt deposits found beneath the Gulf of Mexico are part of the reason why the basin continues to yield new discoveries. But to understand why the Gulf is so rich in oil and gas and why projects such as GBDS are so important to unlocking those energy resources, we have to wind the clock back to a period long ago, when early dinosaurs roamed a single mega-continent known as Pangea.

The basin that was eventually to become the Gulf began forming about 200 million years ago when Pangea split to form Africa and the Americas. Throughout subsequent millennia the basin underwent many changes, including several periods of evaporation that left behind vast blankets of salt, now deposited deep in the Earth’s crust. As the continents continued to pull apart, seawater rushed back in, forming a vast ocean-filled basin stretching from Oklahoma and West Texas all the way down to Guatemala. Sediments eroded from the surrounding continents, eventually forming the Gulf of Mexico as we know it today.

Scientists believe it is this complex geological history that gives the Gulf of Mexico its economic and scientific significance. The salt deposits in particular have been crucial in creating structure in the rock around which oil and gas can form. The salt also provides a seal that allows the oil to collect in vast reservoirs.

“The basin was actually one large salt deposit before it became separated by seafloor spreading,” explains Snedden. “Besides providing trap structure and seal rocks, salt is important because it also preserves oil sources far longer and deeper than you’d expect. It wicks away heat and lowers temperatures, kind of like a dry-fit t-shirt.”

Until the turn of the century no one knew what lay below this salt canopy. It wasn’t until technology allowed scientists to peer beneath the salt that the oil and gas was revealed. Significantly, the salt deposits in the southern Gulf of Mexico are much more complex than those found in the north. This is where detailed depositional maps of the region will be a critical advantage for successful exploration in the future.

By bringing together research expertise from across the UT Jackson School of Geoscience, GBDS can continue to offer companies information about the Earth’s history that allows them to explore previously inaccessible resources. And by offering increasingly innovative and detailed data sources, GBDS has not only attracted the likes of Repsol back to the program, but brought on new billion-dollar partners including EOG, Fieldwood, Kosmos and Hilcorp.

GBDS’s contributions to science will no doubt long outlast many of the twenty-four industry members and perhaps even the oil industry itself. One more contribution will be demonstrated at the meeting with the announcement of a forthcoming book by Snedden and Bill Galloway, titled The Gulf of Mexico Sedimentary Basin: Depositional Evolution and Petroleum Applications. The book, due to be published by Cambridge University Press later in 2019, essentially distills twenty-four years of GBDS work into a single textbook covering the entire geological history of basin reservoirs, source rocks, and associated tectonics in the Gulf of Mexico.

The GBDS Annual Industrial Associates Meeting takes place January 17, 2019 at the UT Institute for Geophysics, AUSTIN, TEXAS.