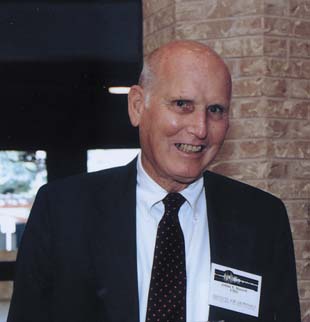

On August 21, 2019, the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics and the world of ocean sciences lost a luminary leader and pioneering geophysicist.

Arthur (Art) Maxwell served as director from 1982 to 1994. His colleagues remember an inspirational man of science who cared greatly about the Institute and its people.

“You always felt like he was looking after everyone,” said Craig Fulthorpe, a senior research scientist who joined UTIG in 1990. “He was a compassionate man who cared about people.”

When Maxwell brought UTIG to Austin from Galveston, one of his first actions was to begin hiring a new cadre of scientists, tripling the number of research staff and bringing a fivefold increase in graduate students. The new personnel helped build collaborations with other universities and, alongside Maxwell’s tireless advocacy, greatly increased funding from state and private sources.

Lawrence Lawver was one of these early hires, joining UTIG from MIT to begin work that would eventually lead to the PLATES program, a significant milestone in the study of plate tectonics that has also attracted thirty years of industry funding.

“Art Maxwell regularly asked how I was doing, what I was working on and how he could help me reach my goals,” remembered Lawver. “He was truly a great leader.”

Maxwell’s mindset and approach to administration was unique for its day because it was geared to providing scientists with the resources to be creative.

Ian Dalziel, a senior UTIG researcher who first met Maxwell when he joined the Institute in 1985 said that under Maxwell’s leadership, UTIG developed an entrepreneurial environment at UTIG which exists to this day.

“Art really was the initiator of the modern UTIG,” he said. “He encouraged you to follow your instincts as a scientist. He was a really inspirational guy.”

Maxwell’s program of hires was conducted strategically to create new research groups and initiatives that greatly increased the Institute’s research scope.

Important hires included Don Blankenship, who introduced airborne geophysics to the Institute and Paul Stoffa, who would not only become UTIG’s director for 14 years following Maxwell’s retirement but also triggered a new era in computational geophysics at UT.

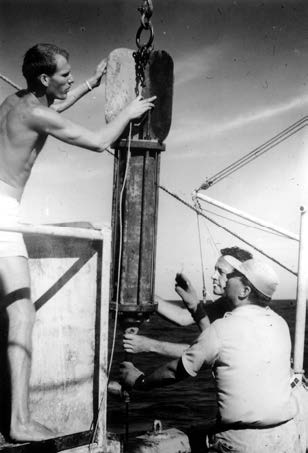

Maxwell’s own scientific research will be best remembered for producing some of the first direct geological evidence to support the now widely accepted process of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics, as well as his role in starting scientific ocean drilling.

Mrinal Sen, who was hired by Maxwell to work alongside Stoffa, said that Maxwell was more than just a brilliant ocean scientist. He was a leader whose honesty and character made him instantly approachable. “It was very easy to talk to him because he meant everything he said,” said Mrinal Sen, who is now a Professor and Associate Director at UTIG. “He was very upfront and frank, I liked this about him.”

Yosio Nakamura, Professor Emeritus and pioneer of planetary science, remembers a hands-on leader who led from the front. “Art was always very interested in what we were doing and encouraged what we did,” he said. “What I really liked was that he sometimes joined us when we were on (scientific) ocean cruises. He was great, I have only good memories of him.”

The effect Maxwell had on the people he met and worked with will always remain a high watermark for leadership at UTIG. The staff and students at UTIG are forever grateful and proud to be a part of the legacy of Arthur E Maxwell.

Cliff Frohlich, senior research scientist emeritus, joined UTIG in 1978 and remained until he retired in 2017.

Art came to UT soon after my scientific career began, and he taught me a lot about how to be an effective scientist and administrator.

Early on, whenever I identified a problem at UTIG I would go in to see Art (his door was always open) and tell him about the problem. I could never figure out why he didn’t seem glad to see me! This changed when I learned that I was much more welcome when I would describe a problem and then outline a straightforward solution. “Cliff, thanks for letting me know about this,” he would say.

When there were staff meetings to discuss decisions that needed to be made concerning major initiatives or new hires, Art would take out his pipe and call for discussion. The young hotheads like myself (and sometimes, the more senior hotheads) would spend the next hour or more in loud, heated arguments about the right choice, while Art just listened silently, sucking on his unlit pipe. Then, after we all got tired and had nothing more to say, Art would speak, announcing his decision, enlightened by those few fragments of wisdom from the great volumes of words we had provided, and having given all of us an opportunity to have our say. It was just plain fair to all about how Art had reached his decision, and we generally accepted it.”

Frohlich said that when Maxwell was forced to deal with conflict with other University departments he was as gracious in defeat as he was magnanimous.

At least once I saw him lose such a conflict in a fashion such that I felt Art had been insulted and misused by his adversary. I remember thinking, “Art will never work with this person again. They hate each other. They’re done.” Yet, only a few months later, Art and this person were collaborating to build a new program that was good for both organizations. And I learned that for Art Maxwell, it was never just about winning, or ego, or holding a grudge. Art didn’t hate anybody, ever. For Art Maxwell, it was about what was best for UTIG, for science, and for the University.”

If you have a memory or picture of Art Maxwell that you would like to contribute to this story please send to: social@ig.utexas.edu