Global warming is approaching a tipping point that during this century could reawaken an ancient climate pattern similar to El Niño in the Indian Ocean, new research led by scientists from The University of Texas at Austin has found.

If it comes to pass, floods, storms and drought are likely to worsen and become more regular, disproportionately affecting populations most vulnerable to climate change.

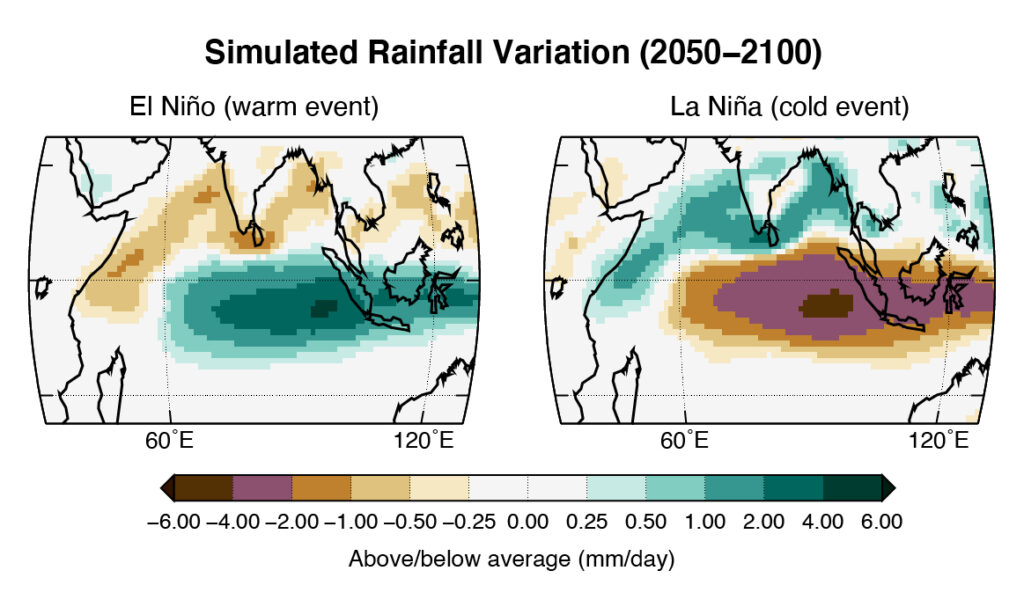

Computer simulations of climate change during the second half of the century show that global warming could disturb the Indian Ocean’s surface temperatures, causing them to rise and fall year to year much more steeply than they do today. The seesaw pattern is strikingly similar to El Niño, a climate phenomenon that occurs in the Pacific Ocean and affects weather globally.

“Our research shows that raising or lowering the average global temperature just a few degrees triggers the Indian Ocean to operate exactly the same as the other tropical oceans, with less uniform surface temperatures across the equator, more variable climate, and with its own El Niño,” said lead author Pedro DiNezio, a climate scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, a research unit of the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

According to the research, if current warming trends continue, an Indian Ocean El Niño could emerge as early as 2050.

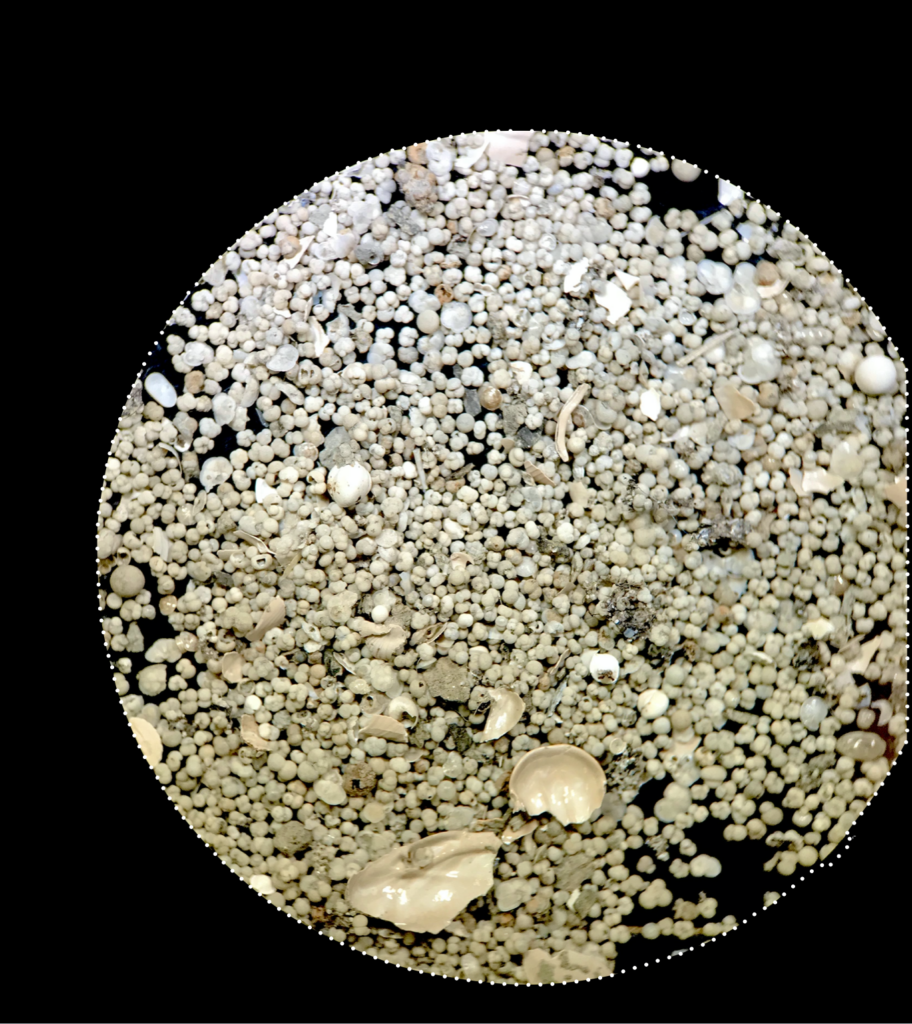

The results, which were published May 6 in the journal Science Advances, build on a 2019 paper by many of the same authors who found evidence of a past Indian Ocean El Niño hidden in the shells of microscopic sea life, called forams, that lived 21,000 years ago — the peak of the last ice age when the Earth was much cooler.

To show whether an Indian Ocean El Niño can occur in a warming world, the scientists analyzed climate simulations, grouping them according to how well they matched present-day observations. When global warming trends were included, the most accurate simulations were those showing an Indian Ocean El Niño emerging by 2100.

“Greenhouse warming is creating a planet that will be completely different from what we know today, or what we have known in the 20th century,” DiNezio said.

The latest findings add to a growing body of evidence that the Indian Ocean has potential to drive much stronger climate swings than it does today.

Co-author Kaustubh Thirumalai, who led the study that discovered evidence of the ice age Indian Ocean El Niño, said that the way glacial conditions affected wind and ocean currents in the Indian Ocean in the past is similar to the way global warming affects them in the simulations.

“This means the present-day Indian Ocean might in fact be unusual,” said Thirumalai, who is an assistant professor at the University of Arizona.

The Indian Ocean today experiences very slight year-to-year climate swings because the prevailing winds blow gently from west to east, keeping ocean conditions stable. According to the simulations, global warming could reverse the direction of these winds, destabilizing the ocean and tipping the climate into swings of warming and cooling akin to the El Niño and La Niña climate phenomena in the Pacific Ocean. The result is new climate extremes across the region, including disruption of the monsoons over East Africa and Asia.

Thirumalai said that a break in the monsoons would be a significant concern for populations dependent on the regular annual rains to grow their food.

For Michael McPhaden, a physical oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who pioneered research into tropical climate variability, the paper highlights the potential for how human-driven climate change can unevenly affect vulnerable populations.

“If greenhouse gas emissions continue on their current trends, by the end of the century, extreme climate events will hit countries surrounding the Indian Ocean, such as Indonesia, Australia and East Africa with increasing intensity,” said McPhaden, who was not involved in the study. “Many developing countries in this region are at heightened risk to these kinds of extreme events even in the modern climate.”

The research was funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant under the NSF Paleoclimate Program.

For more information, contact:

Constantino Panagopulos, 512-574-7376