Adapted from an article by Anne J. Manning at The Harvard Gazette, published April 24, 2024.

Fossil record stretching millions of years shows tiny ocean creatures on the move before Earth heats up

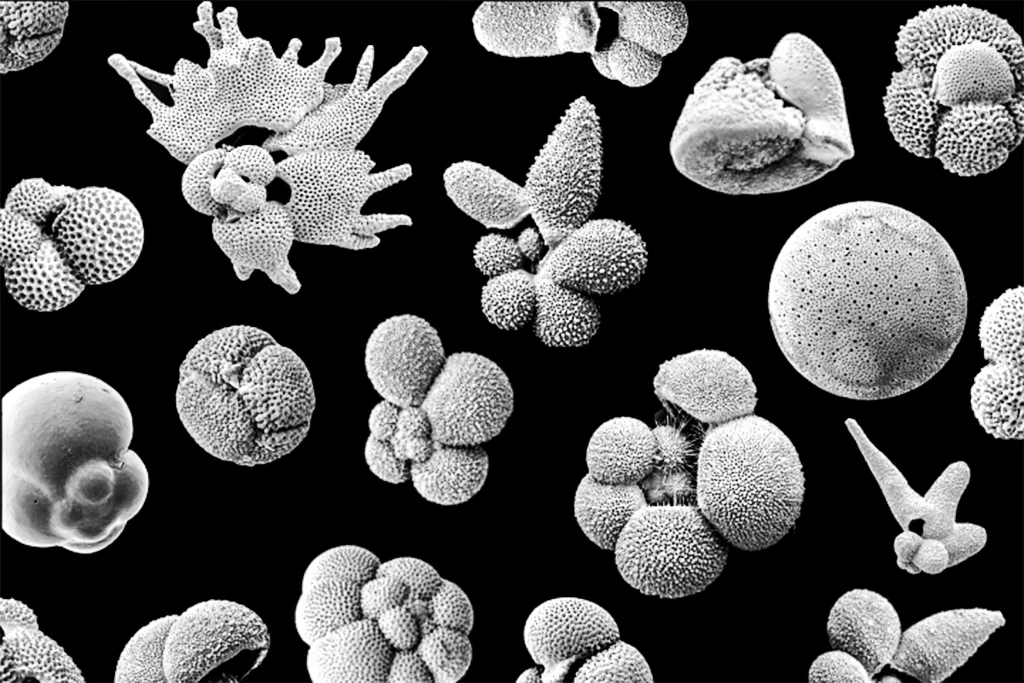

For hundreds of millions of years, the oceans have teemed with single-celled organisms called foraminifera, which are hard-shelled, microscopic creatures at the bottom of the food chain. The fossil record of these primordial specks offers clues into future changes in global biodiversity related to our warming climate.

Using a high-resolution global dataset of these microfossils that’s among the richest biological archives available to science, researchers have found that certain mass extinctions are reliably preceded by subtle changes in how a biological community is composed. Scientists think these changes can act as an early warning signal for these extinction events.

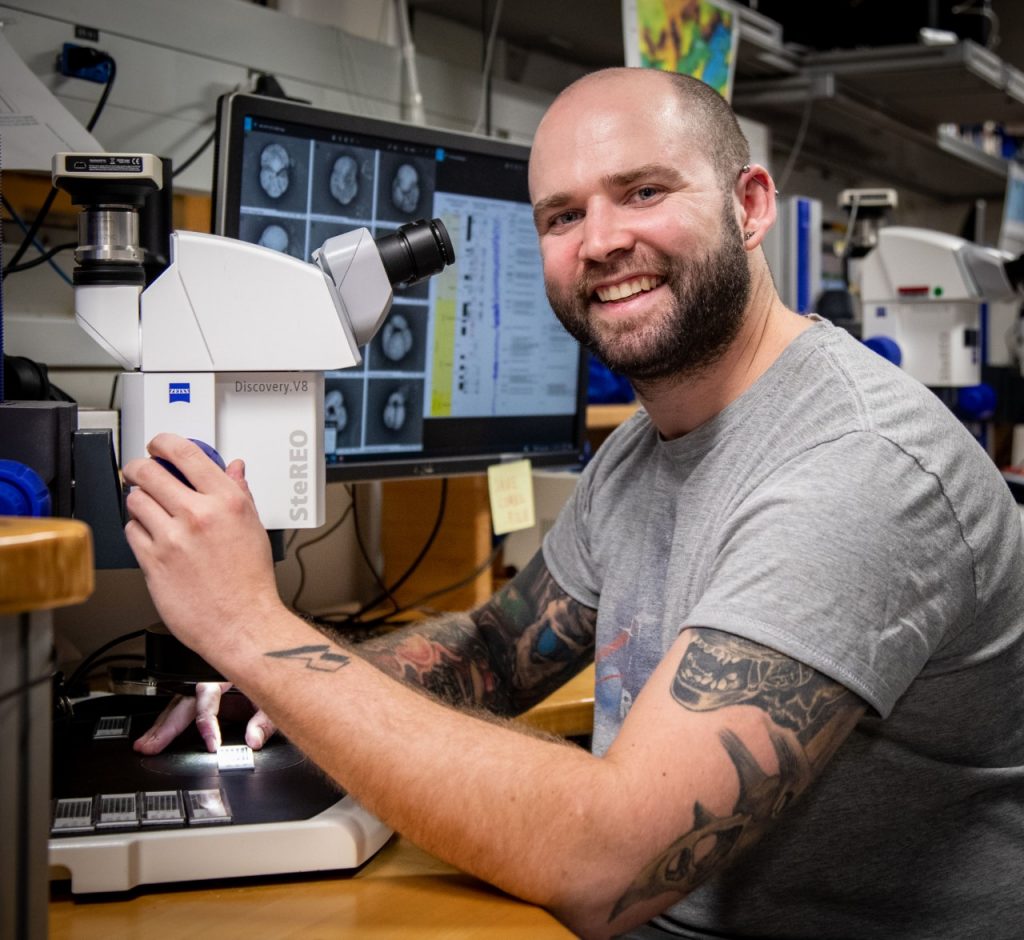

The results are in Nature, with the study co-led by Anshuman Swain, a researcher in Harvard University’s Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, and Adam Woodhouse, formerly a researcher at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics and now at University of Bristol.

Swain, a physicist by training who applies network analysis to biological and paleontological data, teamed up with Woodhouse to probe the global community structure of ancient marine plankton and see if it could serve as an early warning system for future extinction of ocean life.

“Can we leverage the past to understand what might happen in the future, in the context of global change?” Swain said. “Our work offers new insight into how biodiversity responds spatially to global changes in climate, especially during intervals of global warmth, which are relevant to future warming projections.”

The researchers used the Triton database, which was developed by Woodhouse, to ascertain how the composition of foraminifera communities changed over millions of years — a much longer time span than what is typically studied at this scale. They focused on the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum, the last major period of sustained high global temperatures since the dinosaurs that’s analogous to worst-case global warming scenarios.

They found that before an extinction event 34 million years ago, marine communities of foraminifera became highly specialized everywhere but in the southern high latitudes, which implies that these micro-plankton migrated en masse to higher latitudes and away from the tropics. This finding indicates that community-scale changes like the ones seen in these migration patterns are evident in fossil records long before actual extinctions and losses in biodiversity occur.

The researchers think it’s important to monitor the structure of biological communities to predict future extinctions.

According to Swain, the results from the foraminifera studies open avenues of inquiry into other marine life, sharks, and insects. Such studies may spark a revolution in an emerging field called paleoinformatics, which uses large spatiotemporally resolved databases of fossil records to investigate a range of questions, including gleaning new insights into the future Earth.

The study was made possible by a longstanding National Science Foundation field study aboard the JOIDES Resolution research vessel, which over the last 55 years has conducted ocean drilling around the world. The project is set to expire this year.

For more information, contact:

Constantino Panagopulos, University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, 512-574-7376.