Extreme weather is becoming more costly. The University of Texas Institute for Geophysics and insurance services company Verisk have teamed up to better understand where, when and why extreme weather happens, and its future in a warming climate.

BY CONSTANTINO PANAGOPULOS

When Storm Ciarán slammed into Europe in November 2023, it battered the continent with wind, hail and torrential rain. The deadly storm set off wildfires, spawned tornadoes and swept away roads and buildings, leaving 21 dead and causing over 2 billion euros ($2.14 billion USD) in damage.

Intense cyclones like Ciarán are rarely seen in Europe. But the storm was part of a global trend in damaging weather events — including thunderstorms, tornadoes and wildfires — whose impacts are getting worse as the climate warms and populations grow.

This new reality has thrust climate science to the forefront of the insurance industry. Insurance companies were among the first to wake up to the idea that understanding climate change is vital for the future of their business.

That’s true for insurance services company Verisk, which recently warned that insured losses from extreme weather have risen sharply in recent years, and the trend is expected to continue. But exactly how and where it will have the greatest impact is a multibillion-dollar unknown.

What makes extreme weather particularly hard to predict is that reliable storm records go back only a few hundred years. Modern weather observations, barely a few decades. This means scientists just don’t have enough data about freak events such as Ciarán or other kinds of extreme weather events.

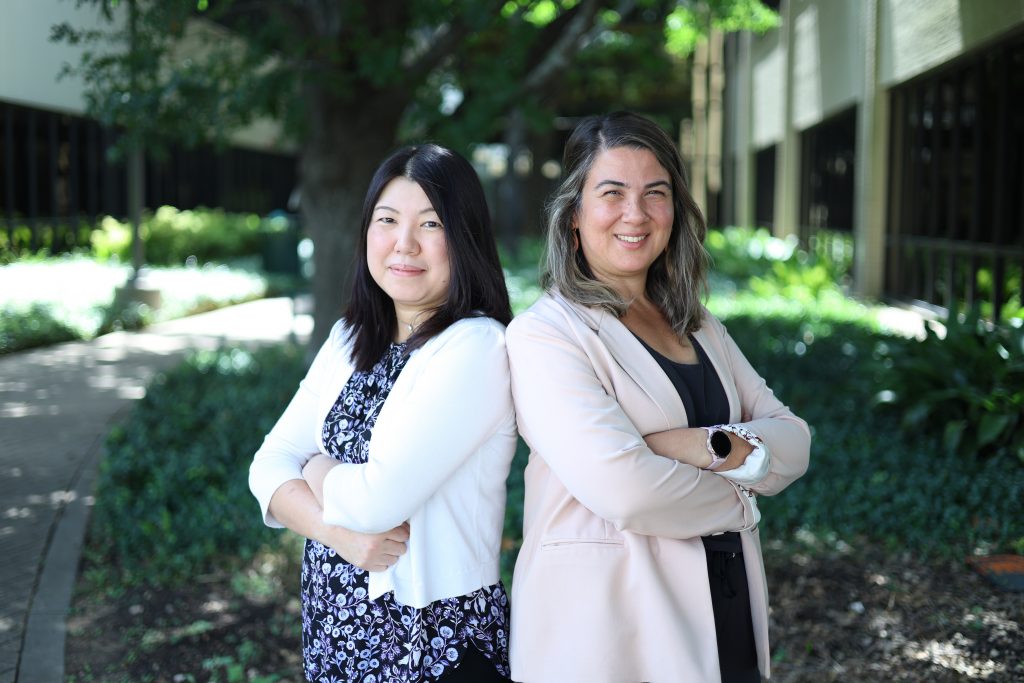

“It’s very hard to make estimates about a one-in-1,000 year event based on observational data,” said Yuko Okumura, a research professor at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG).

It’s important to understand how those (extremes) will change in the future so that we can adapt.”

Danielle Touma

Verisk is partnering with UTIG to solve the problem. Okumura and her team are running a climate simulation on a supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center that will give them 100,000 years’ worth of weather data. Verisk scientists, meanwhile, have developed an artificial intelligence algorithm to improve the simulation’s accuracy and resolution.

The simulation will deliver a huge cache of data that will let Verisk model the full range of weather possibilities in any region. The same data will help UT researchers investigate what drives extreme weather and how it might change in the future.

For Verisk, the project will allow the company to make a technological leap from statistical approximations to a sophisticated physics-derived simulation of every kind of weather the planet can produce.

The three-year project’s goal is to better understand and prepare for what lies around the corner in an era when extreme weather is becoming increasingly destructive and unpredictable. Global warming isn’t the only culprit. Weather impacts are being felt in places that have neither the infrastructure nor resources to defend against them, making deadly events with multibillion dollar price tags much more common.

“They’ve gone through the roof,” said Charles Jackson, a former UTIG climate scientist who now leads Verisk’s global atmospheric perils unit. “There are several reasons why that’s happened, including stronger extremes and a greater fraction of coastal developments becoming exposed to hazardous weather.”

With the stakes so high, it never has been more important to understand the hazards of extreme weather. And with experts on everything from mathematical uncertainty to cascading weather hazards and access to the world’s most powerful academic supercomputers, that’s exactly what UTIG is uniquely poised to do, Okumura said.

“These are current and urgent problems, but UTIG has the expertise and computational resources to help our partners come up with real solutions for the communities they serve,” she said.

Modeling Extremes

Before joining Verisk, Jackson was tackling the mathematics of uncertainty at UTIG. These equations and formulas help manage the chaos of real-world physics in modern climate models. Today, he leads a research team at Verisk that develops similar models to calculate the risk of extreme weather.

These models typically incorporate weather predictions, climate records and other data about a particular place.

The UTIG project offers something different. It uses a global model — which is important because extreme weather in one area can have knock-on effects elsewhere — and it will supply data about very rare weather events that have an outsized impact on potential losses. The information could be very significant for the industry.

“You can have many, many storms in a year that add up to a billion dollars, but then one year you have one big event that’s $100 billion on its own,” Jackson said.

The fear with global warming is that these heavyweight events may begin occurring more frequently or in vulnerable places. But because they don’t happen often enough to show up in shorter climate simulations, they are in effect flying under the radar, Jackson said.

The UTIG project is a major effort to cover that data blind spot. By gathering 100,000 years of simulated climate data, the Verisk researchers will gain information about where the future extreme weather hot spots are likely to be and adjust their risk assessments accordingly.

More precisely, the project isn’t just one simulation. It’s a set of 2,500, each spanning the 44 years from 1979 to 2023. For context, the climate models that inform the reports of the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change use sets of about 10 concurrent simulations.

“Being Texas, we’ve naturally gone super large,” Jackson quipped.

There’s one more trick up Jackson’s sleeve: Verisk’s proprietary machine learning algorithm effectively smooths out flaws in the climate model, making the results more lifelike. That’s because weather is inherently chaotic, and even the tiniest flaw in the model can skew things in ways that only get worse as the simulation progresses.

This kind of artificial intelligence is new to the climate community, but it represents an exciting new set of tools with which to do better science, Jackson said.

For Verisk that means a better understanding of weather risks. For the UTIG researchers it’s a way to learn what drives extreme weather and its connection to climate change.

Cascading Calamity

In 2023, unusually strong winds fanned fires that destroyed Lahaina, Hawaii, and killed 101 people. A similar firestorm killed 104 people in a seaside village outside Athens in 2018.

In both instances, environmental conditions converged to turn a dangerous event into a catastrophe, said Danielle Touma, a research assistant professor at UTIG and a member of Okumura’s team.

“It was only with that combination of very dry weather, lightning strikes and high winds that a spark became an inferno that engulfed (Lahaina) within a few hours,” she said.

Touma is an expert on extreme weather. She studies the causes of extremes and how one catastrophe can build on another, such as heavy rain setting off landslides after a wildfire.

One of her roles on the project is to decide what defines an extreme event. That includes storms, wildfires and flashfloods, but also less obvious conditions that can still have severe impacts on people and the environment.

For example, prolonged heat waves can destroy crops, dry up reservoirs, overload energy grids and harm the most vulnerable. But heat waves are especially deadly when paired with a blast of humidity, Touma said.

“If humidity is above a certain amount, sweat can’t evaporate as quickly, and so, our bodies just can’t cool,” she said. “That’s why we’ve included humidity in the data we’re collecting from the simulations.”

For Touma, the simulations are an opportunity to understand the part played by climate change. For each run of the simulation, the researchers tweak the atmosphere less than a trillionth of a degree. It’s a tiny change, but the chaotic nature of weather means that each variation lets the simulation play out in a unique way without altering global warming’s overall influence. That lets them separate statistical anomalies (like rolling 100 sixes in a row) from longer- term warming trends (a loaded dice).

“It’s important to understand how those (extremes) will change in the future so that we can adapt, and to understand the consequences of not mitigating greenhouse gas emissions,” Touma said.

Variable Climate

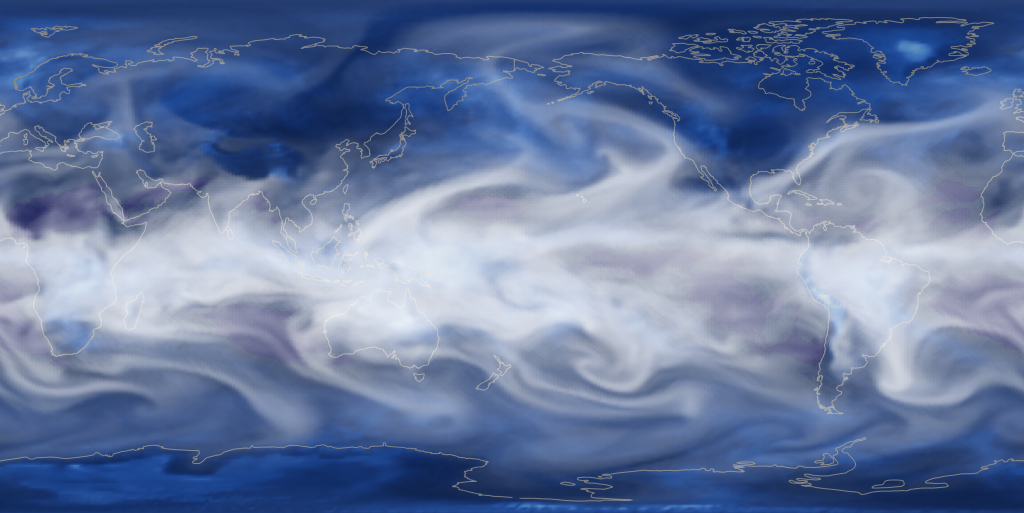

Global warming isn’t the only driver of extreme weather. Natural climate swings were setting the stage for extreme weather long before people came on the scene. The hot and cold seesaw between El Niño and La Niña is such a strong driver of global weather that for decades, it obscured the impact of human-driven global warming.

The new simulations will help UTIG researchers separate trends in extreme weather that are caused by natural climate variability and those ultimately linked to greenhouse gas emissions.

The opportunity to decipher climate variability and extreme weather is what makes the new simulations so important, Okumura said. Picking apart these patterns to get at the underlying climate hazard is what drives the UTIG research.

“We might look at El Niño and say we’ll have 1 millimeter more rainfall per day in Texas over the course of a season,” she said. “But what does that mean? If it is spread evenly, it is great for agriculture, but if it all falls at once, then you could have flash floods.”

When the simulations are complete, the UTIG researchers hope to have enough data showing how El Niño is changing and how that will affect extreme weather.

They’ll also tackle other climate swings such as El Niño’s fickle northern cousin, the North Atlantic Oscillation, which sets the baseline for winter weather in North America and Europe.

That’s of particular interest to Jackson and the Verisk team because their initial focus is to develop atmospheric peril models — winter storm, summer storm and flood models — for the European market. After that, they’ll move on to other regions.

“The combination of expertise in climate modeling, plus the high- performance computing resources and the knowhow to get the most out of them, is very rare to find in one place, but it’s all right there at the University of Texas,” Jackson said.

The simulations are still running, but when complete, the huge cache of data will let Verisk prepare for climate disasters and help UT researchers answer questions about the future of extreme weather.

First published in the Jackson School of Geosciences Newsletter, 2024.