Backpack, hat and rock-hammer in hand: the archetypal geologist has attracted generations of outdoor-loving people to the geosciences. But it’s an image that people like Thorsten Becker, a professor at The University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences and this year’s recipient of the International Lithosphere Program’s Evgueni Burov Medal, hope to change.

“Many of us love being in the field,” Becker said, “but being a geoscientist isn’t all about camping, drinking beers and swinging hammers. There’s a lot of different ways to do geoscience.”

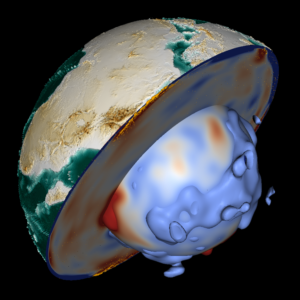

Becker is a computational geoscientist who develops mathematical models to show how the ebb and flow of Earth’s deep interior influences earthquakes and shapes the landscape around us. Like many geoscientists, he has spent plenty of time doing fieldwork, but his own research mostly involves working with computers.

Becker wants to see more people interested in computational approaches to geosciences. He also wants to see more done to level the playing field in terms of K-12 education. His solution is to reach students who never went camping as kids, or never took a calculus class, and offer them a way into the geosciences.

“My latest NSF FRES (a federal funding program for frontier research) proposal includes collaborative work with Dana Thomas (the Jackson School’s outreach coordinator) and the Texas Advanced Computer Center to build a set of instructional materials that will make it easier for geoscience undergraduates and graduates to learn math skills along the way,” he said.

Another effort is Lab to Planet, a new class he is hoping to co-teach with Jackson School Professor Peter Flemings.

Like the frontier research proposal, Lab to Planet was designed for students with little prior knowledge of math, physics and geology in mind. Instead, the course teaches those skills alongside lab experiments and theory about Earth dynamics. Becker hopes that this approach can motivate students to understand why math concepts are important.

“If you’ve never seen a derivative or don’t know what a matrix is, we’ll take some time to explain what they are along the way,” he said. “Learning these concepts when you need them can help you see why you should care about linear algebra or calculus.”

Dropping prerequisites means the course is a step into the geosciences for students from any background. That’s important for Becker because he believes anyone can be a geoscientist, regardless of experience or interests.

“If we bring more people to the geosciences with different backgrounds and perspectives it will make the field much more exciting and that will lead to better science,” he said.

It’s all part of Becker’s belief that changing the geosciences’ image and demonstrating the discipline’s diversity of career opportunities will create a more diverse and equitable community at all levels of the geosciences, from undergrad to professor.

“I think by making it clear that there are many different ways to be a geoscientist we can provide different entryways for people with all kinds of different talents,” Becker said, “and that can only be a good thing.”